We feel investors should have an information outlet for the financial markets that is thorough, but does not require a prerequisite degree in economics. We hope this makes our commentary informative and educational for all levels of investors. We have also included a glossary at the end of this commentary that defines terms marked with an asterisk (*).

Quarterly Spotlight: Brexit Vote and Impact

Like many of the quarters in the recent past, a single event defined the 2nd quarter of 2016: the United Kingdom’s referendum vote to leave the European Union in late June (colloquially know as “Brexit”). Prior to the Brexit vote, markets had been in a fairly docile state as company earnings from the 1st quarter had, on average, matched the analyst expectations and the price of oil ascended to and steadied around the $50 per barrel mark. The rise in oil prices played a significant role in the strong performance of commodities, while the continuation of depressed interest rates resulted in another quarter of positive bond returns (bond prices move inversely to interest rates.)

| Asset Class† | 2nd Quarter 2016 Return |

| Commodities | 12.8% |

| U.S. Small Cap Stocks | 3.8% |

| U.S. Large Cap Stocks | 2.5% |

| U.S. Bonds | 2.2% |

| International Stocks | -0.6% |

The “leave” vote by a majority of Britons wreaked havoc on nearly all equity markets including the U.S. where the S&P 500 lost nearly 6% in a 2-day period, only to regain all that was lost in the week ending the quarter. The reason for such a sharp decline followed by an almost equally sharp rebound likely had more to do with the unexpectedness of the result, rather than the result itself. All major polling leading up to the vote had pointed to the “remain” camp winning, and as often happens when unexpected news hits, markets reacted in a violent manner.

That is not so say that the result of the U.K. leaving the EU does not have repercussions, but rather it may take some time to determine exactly how the process of leaving the EU pans out. Since this is an unprecedented event, it is largely unknown how issues relating to finance such as trade agreements and currency movements will be resolved, but early indications are that the process will play out over a long time period.

Commentary: Emergence of Negative Interest Rates

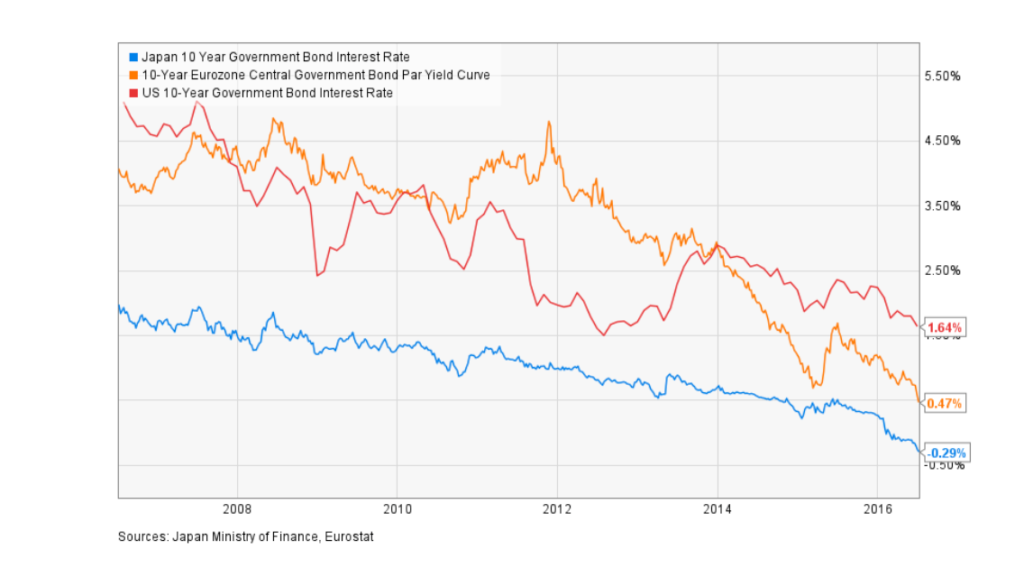

Since the end of the 2008 financial crisis, it has been well documented that interest rates across the globe have been on a downward trajectory. By utilizing Monetary policy* to affect interest rates, central banks have made borrowing money less expensive, which was intended to stimulate economies. However, something strange has recently occurred where some European and Japanese bonds are sporting negative interest rates. This phenomenon breaks even the most elementary principles of economics and banking–since savers are expected to earn interest and borrowers are expected to pay interest.

See the table below to see how this negative interest rate trend is impacting recent interest rate curves in Japan, Europe and the US.

While the interest rate on government bonds does affect the rates at which individuals and businesses can borrow, we are still far away from negative rates creeping into everyday financial life (though you can always still dream of getting paid to have a mortgage). In the current context of economic thought, zero was always assumed to be the lowest point that interest rates could go. However, this downward trending environment is disproving this theory–which is bringing up the question of how we can prepare for the future within our current understanding of economics. Since the birth of economics as a social science, trends and eras of economic principle have evolved slowly as the world and cultures changed. In fact, these recent spreading beliefs of Monetarist economics are relatively new, only reaching the mainstream in the past half century. Right now this small slice of economic history is seeing a lot of change in a short amount of time. It is too early to tell if this is merely a blip in the history of economics or whether it may be the beginning of a longer new era, where new theories must be tested.

Glossary

Monetarist Economics/Monetary Policy – Economic theory mainly associated with economist Milton Friedman, that centers around central banks, like the U.S. Federal Reserve, using their power to manipulate interest rates in order to achieve a desired set of results such as full employment or low inflation.

† Indices used to represent asset classes:

U.S. Large Cap Stocks – S&P 500

U.S. Small Cap Stocks – Russell 2000

International Stocks – MSCI ACWI ex-U.S.

U.S. Bonds – Barclays Aggregate

Commodities – Bloomberg Commodity

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

The information presented here is not specific to any individual’s personal circumstances.

To the extent that this material concerns tax matters, it is not intended or written to be used, and cannot be used, by a taxpayer for the purpose of avoiding penalties that may be imposed by law. Each taxpayer should seek independent advice from a tax professional based on his or her individual circumstances.

These materials are provided for general information and educational purposes and represents Wilson Capital’s views based upon publicly available information from sources believed to be reliable—we cannot assure the accuracy or completeness of these materials. The information in these materials may change at any time and without notice.

Wilson Capital is a Registered Investment Advisor (“RIA”), registered in the state of Massachusetts. Wilson Capital provides asset management and related services for clients nationally. Wilson Capital will file and maintain all applicable licenses as required by the state securities boards and/or the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”), as applicable. Wilson Capital renders individualized responses to persons in a particular state only after complying with the state’s regulatory requirements, or pursuant to an applicable state exemption or exclusion.

Click here to download a printable PDF of this letter: 2Q16-Investment-Letter-FINAL-72016.pdf (477 downloads )